What is a “greenway”? A greenway is a multi-use active transportation corridor for people who are walking, running, rolling, riding a scooter, pushing a stroller, and it is green – ideally a park-like setting with trees for cooling neighborhoods and soaking up stormwater. (Boston area examples include the Minuteman Bike Path, the Paul Dudley White Bike Path along the Charles, and the Southwest Corridor Park.) A greenway “system” is a network of such paths that together unlock tremendous recreational and transportation potential. On-street links between greenways are critical to knitting this network together.

Our Park Legacy

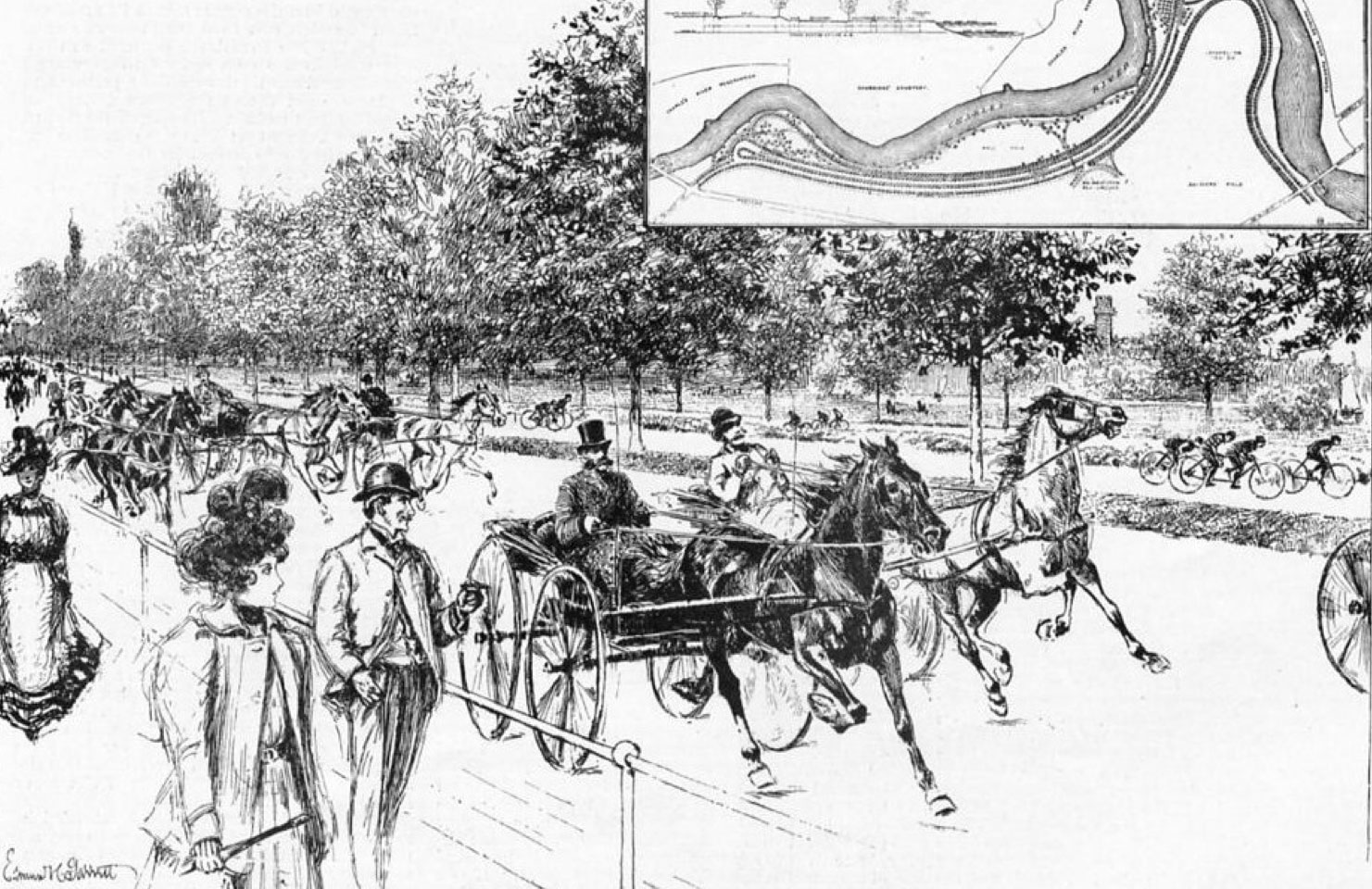

The idea of a metropolitan greenway system was largely invented right here in Boston in the late 19th Century by two leaders of the urban parks movement: Frederick Law Olmsted and his protege, Charles Eliot.

The idea was to use tree-lined pleasure drives and linear parks to knit together the region’s best landscape features into a network accessible to all. Unlike the squares, plazas, royal grounds, and gated parks of Europe, this greenway network was a distinctly democratic and American invention. It was intended to connect together people from all walks of life and all parts of the city in a shared experience of the outdoors.

Olmsted worked on the Emerald Necklace for close to twenty years (1878-1896) and considered it his most important work. When Olmsted moved from New York to Brookline to be closer to the project, Charles Eliot joined the firm. It was here that he was trained in the new profession of landscape architecture and came to appreciate the importance of interconnected park systems. In the 1893 Eliot, working with some of the leading intellectuals and political leaders of the day, convinced the state legislature to establish a Metropolitan Parks Commission (now the Massachusetts Department of Conservation and Recreation or DCR). The Metropolitan Parks Commission was charged with preserving and linking together the distinctive landscapes of Greater Boston from the Middlesex Fells in the north to the Blue Hills in the south and from the Upper Charles River Basin in the west to the islands of Boston Harbor in the east. (The monument to Charles Eliot on the Esplanade lists the major parks and reservations preserved as a result of his work). Eliot took Olmsted’s park necklace and scaled it up to become a regional network of parkways and linear parks. Today, despite the encroachments of the highway system, residents of Greater Boston still enjoy the beautiful parks and parkways of the metropolitan park system.

What 20th Century Car Culture Has Wrought

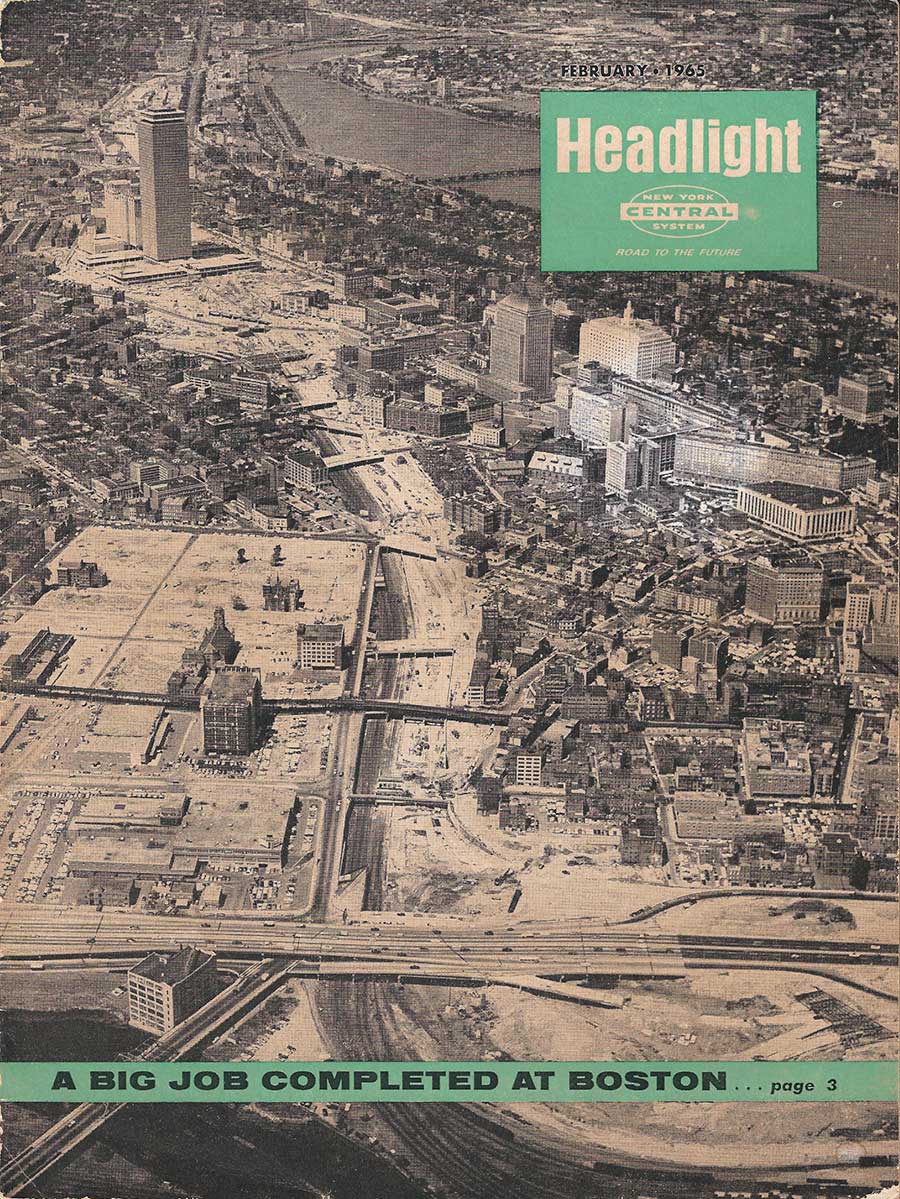

The volume and speed of automobiles increased with each successive decade of the 20th and began to overwhelm the balanced system of paths and parkways laid out out by the park planners of the late 19th century. The broad curves of the original treelined parkways, so pleasurable to travel and pleasing to the eye, were too easily adapted to high speed automobiles. These parkways were widened to accommodate cars and mature shade trees – which highway engineers termed “vertical hazards” – were cut down. Rather than linking people to parks, these historic parkways became major barriers to people on foot or on bike who wanted to access the parks.

In addition, the construction of limited-access highways following the path of least resistance along the rivers and shores, further eroded and isolated Eliot’s original park system. The banner photo above shows the impact of Route 128 on the upper Charles River Reservation in Weston and Newton.

Storrow Drive at the heart of the city is another infamous example. In the early 1930s, Hellen Storrow made a million dollar gift to the state to build a linear park along the Charles River Basin to honor her husband whose earlier advocacy had led to the damming of the river in 1910. Less than fifteen years after the park opened, the state legislature voted to build a limited access highway along the river severing the Esplanade from the neighborhood. They then had the temerity to name the highway after Mr. Storrow.

Compensatory parkland was built out into the basin forming a series of lagoons but the damage was done. There have been many efforts to bridge this barrier over the years include the Author Fiedler pedestrian bridge and, most recently, the Frances Appleton Pedestrian Bridge.

The tide of support for highway construction began to turn in the late 1960s and 1970s with the cancelation of the Southwest Expressway and the construction of the Southwest Corridor Park. This was the first step towards the reinvention of a greenway system for Boston.

A Greener Future

Two decades into the new millennium, momentum is building around reclaiming and expanding a multi-use greenway system for Greater Boston. Olmsted and Eliot’s idea of an interconnected park system is being expanded and reinterpreted for the 21st century. Several break-through projects are on the drawing boards including final design for the Northern Strand rail-trail to the north and preliminary design for overcoming the dual barriers of I-90 and I-95 to the west at Riverside. The growing consensus on the value of greenways has gained greater urgency due to three things: climate, traffic, and health.

A new generation of leaders attuned to these three imperatives are making their way into leadership roles in state agencies, public office, non-profit organizations, and private businesses. For each new greenway project that is brought forward today, what might have been a protracted battle for recognition years ago, is instead becoming a thoughtful conversation about shared resources. It’s no longer a question of “what and why” but “when and how.”

A reboot or reinvention of Olmsted and Eliot’s 19th century metropolitan park system has been underway for fifteen years now. It is a greenway system for the 21st century that goes by several names including the Landlines Network, Emerald Network, and Green Links. What these overlapping visions have in common is the burning desire to bring safe protected routes within reach of every neighborhood in the Boston metropolitan area and to have those greenways shared widely by a diverse group of people. This is a democratic vision routed in our American experience going back to the beginning of the parks movement.

In the not too distant future, a child will be able to wake up on a weekend morning in Roxbury or in Everett and be able to bike with their family along safe greenway paths to a river park or a seashore beach. Later in the week those same greenway paths will carry people to work. This idea of a greenway network is low-tech and low-cost and in some ways old fashioned, but it is a powerful idea that gains more energy as it builds out. With patience, persistence, and intergenerational leadership this is happening today.